Dudley Culp first saw clogging in spring 1971 at the World ’ s Championship Old Time Fiddlers Convention in Union Grove, North Carolina. He had just graduated from East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C., and was working as director of the REAL House, a local counseling center. When he saw Haywood County, N.C.'s Smokey Mountain Cloggers perform, he felt swept into their energy: sixteen young dancers, all in step with each other, looking like they were having fun. He knew he had to learn how to do what they were doing.

Dudley asked several people around camp to show him a step, but they wouldn’t or couldn’t explain what they were doing with their feet --until he met Evelyn Smith Farmer of Fries, Virginia. She showed him a step with a heel-toe shuffle and a weight change so he could alternate his right and left feet to keep the step going. He brought it back to Greenville, where he annoyed his housemates practicing and shared it with friends, hoping to start his own team and dance at Union Grove the next year. But first, he needed to learn some figures.

In the summer of 1971, Dudley and Toni Jordan (now Williams), a friend from the circle of free-spirited hippie-type students, took a square dance class from Jo Saunders in ECU’s Wright Auditorium. Dr. Ralph Steele, a recreation professor, heard they were starting a dance team and referred students to them. He also connected them with Betty Casey, an internationally-experienced square dance caller who had moved to Greenville because of her husband’s Voice of America assignment. Another element that helped the dancers was their connection to the Flatland Family Band, one of several local old-time and bluegrass bands with student/faculty/community members: Carolyn Creekmore (vocals, autoharp), Skeet Creekmore (banjo, ECU Special Education), Bill Joyner (banjo), Linda O’Connor (guitar), Mike O’Connor (fiddle, ECU Geology), and Stan Riggs (bass, ECU Geology/Coastal Studies).

Lelft: Duley Culp, circa 1972; Top: Smoky Mountain Cloggers, from Sittin’ on Top of the World: At the Fiddler’s Convention (film, Sandra Sutton and Max Kalmanowicz, 1974).

Toni Jordan, from 12-19-1971 The Daily Reflector, photo by John Casey.

Jo Saunders & Ralph Steele, from 1972 Buccaneer, ECU yearbook.

Later in the summer of 1971, Toni saw a news announcement about the Autumn Square-Up, a dance-focused festival and competition near Union Grove held in September at the Fiddler’s Grove event site. Neither she nor Dudley had a car, so they got a friend, Robby McLawhorn, to drive them. The Square-Up was one of several events Harper and Wansie Van Hoy hosted at Fiddler’s Grove throughout the year, and the event Dudley, Toni, and Robby found was smaller than the Union Grove festival held on Easter Weekend at J. Pierce Van Hoy’s farm.

Back in 1924, teacher H.P. Van Hoy started the Old Time Fiddlers Convention as a school fundraiser, and it continued as an annual event. In the later 1950s and into the sixties, youth interested in the Folk Movement flocked to the festival from all over the country, often to learn tunes from older musicians, but sometimes just for the party. The festival outgrew the school building and expanded into a circus tent. Some local residents were wary of the counterculture youth, and the festival had to move.

Evelyn Smith Farmer, from Music Makers of the Blue Ridge Plateau (Arcadia, 2008).

Betty Casey, from 12-19-1971 The Daily Reflector, photo by John Casey.

Flatland Family Band, from 12-19-1971 The Daily Reflector, photo by John Casey.

H.P.’s sons J. Pierce and Harper were involved in the festival planning, and both had differing ideas about the atmosphere at the festival’s next home--large vs. small--so, they sponsored both styles, both on Easter Weekend for several years. J. Pierce organized the large World’s Championship Old Time Fiddlers Convention at his farm east of Interstate 77, and Harper organized the smaller Ole Time & Bluegrass Fiddler’s Festival at his Fiddler’s Grove venue west of I-77. The Autumn Square-Up at Harper’s site featured smooth dance and percussive dance styles that were popularized, and standardized to an extent, through the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival that Bascom Lamar Lunsford founded in Asheville in 1928, four years after the initial fiddlers convention in Union Grove.

H.P. Van Hoy, from 3-15-1972 The State, photo by C.G. Mathis Jr.

Tent at Union Grove School, 1968, photo by Fred Robbins.

J.P. & Harper Van Hoy, from 3-15-1972 The State, photos by C.G. Mathis Jr.

Unlike some roots of folk culture that can't be clearly identified, the development of team clogging can be traced from Lunsford’s festival. The competition atmosphere there led to the combination of two dance forms that had been separate: group dancing in round and square figures at social gatherings, even at home--and improvised solo percussive dancing, often called flatfooting. With the introduction of the competition elements, social dancing became performance, making dancers mindful of an audience, competitors, and especially judges. Before the shift towards performance, people wore what clothes they had, and the goal of dancing was enjoyment, and perhaps to impress a person someone liked. In competition, however, winning awarded validation to some groups over others, and encouraged imitation of top-placing groups as well as innovations to dethrone them--such as adding percussive steps to the figures, initially at random, and then becoming more precision, with everyone doing the same steps at the same time in the same style. The publicity also became advertising opportunities for companies who funded costumes--which eventually became identical and often fancy with crinolines.

By the time Dudley and his friends were at the Square-Up in September 1971, three stylistic divisions had developed: smooth dancing (figures without percussive footwork), traditional clogging (figures with irregular percussive footwork), and precision clogging (sameness in dress and percussive steps, with some deviation from partner-based figures). And the Square-Up at Fiddler’s Grove showcased all three. Dudley and Toni watched the teams, analyzed what they liked and didn’t like, and thought about what they could see themselves wearing and doing on stage. With their counterculture sensibility, they valued individuality and reality over coordinated homogeny for the stage. As young people, they were also used to frugality. So, in December at their first performance as the Green Grass Cloggers, they wore clothes they already had. Toni had suggested the name Green Grass Cloggers back in October, and they knew it was right--a reference to Greenville, bluegrass, and the counterculture.

Bascom Lamar Lunsford, June 1957, photo by Hugh Morton.

They soon got more performance opportunities--often at the Attic nightclub in downtown Greenville with the Flatland Family Band--and started discussing costumes. Crinolines, crew cuts, beehives, and identical costumes were out. For dresses, the ladies chose calico instead of gingham because it seemed more organic to them, and the gents wore jeans they already had and added calico yokes to western work shirts. Many of them bought shoes at thrift stores. Their decisions for costumes and dance style transferred their offstage personalities and energy to their performances: they were a team of dancers, but they were still all individuals.

On April 1, 1972, the group debuted at Union Grove, dancing a routine Dudley wrote from figures they’d learned from Betty Casey, the “basic step” Dudley learned from Evelyn Farmer, and other steps the group members developed. The audience cheered loudly, and the cloggers knew they wanted to keep dancing. Later that Fall, the cloggers returned to the Autumn Square-Up--this time as competitors--and the hippie college students from Greenville won a World Champion title against the teams they had tried hard to not be.

In Greenville, the cloggers were removed from concentrations of old time music and solo rhythmic dance practitioners. By that time, most people identified figured group dancing with the mountains. The assumption was not unreasonable, but it wasn’t exactly right either. Isolated rural areas in Eastern North Carolina had ongoing traditions of old-time music as well as group figure dancing and solo rhythmic dancing. But the practices were fading, so local Greenville bands, as well as the cloggers, were mostly revivalists rather than people who had grown up learning from and playing with their families. In their earliest months of learning figures and adding footwork to the figures, the cloggers used what they knew and created what they wanted and needed--and that improvisation itself makes what they were doing a folk art form.

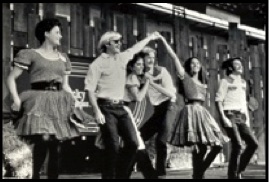

Green Grass Cloggers at first performance, 1971, from 12-19-1971 The Daily Reflector, photo by John Casey.

Green Grass Cloggers, 1974 Charlotte-Mecklenburg Fiddler’s Convention, from the Doug Baker Collection.

Green Grass Cloggers at Union Grove, 1972, photo by Toni Jordan.

Patt Jett and Doug Baker at Union Grove, 1974, from the Doug Baker Collection.

At Union Grove ’73, the cloggers met Willard Watson, a flatfooter who taught them more steps. A few weeks later at another festival near Charlotte, NC, they met Tommy Jarrell, a fiddler and banjo player who became a magnet for people who wanted to learn Round Peak style old-time music, which is now a predominant style of “old-time” music recognized around the world. In Tommy’s musical phrasing, the cloggers felt an energy--and started learning how old-time music was meant for dancing, while the bluegrass they’d known in Greenville was a spectator genre. Several cloggers were inspired to start learning to play instruments to be more connected with the culture that fascinated them.

Both Watson and Jarrell were attracted to the cloggers’ youthful energy and told them their spirit on and off stage reminded them of the way dancing used to be--meaning, before the performance atmosphere had such an influence on stylistic evolution. The cloggers had put together what they could--square figures and improvised steps--and they felt validated in knowing that what they’d created with the intention to be different from the norm was actually recapturing a more earthy spirit of the dance. They had both adopted a culture and been adopted into it.

While the Green Grass members knew they were different, their positive reception at the Square-Up competition and the reception from people like Jarrell and Watson led them to believe they’d be well received at the Mountain Dance & Folk Festival, too. In 1973 and 1974, the audiences enjoyed their performances, but the judges didn’t know how to compare them stylistically to the other groups--even after they added more of the required figures the second year--and disqualified them. But they were invited to give exhibitions instead.

With more invitations to dance at festivals, even before they stopped competing, they needed communal transportation since many of them didn’t own reliable vehicles. In 1973, they bought the first of three busses--a 1950s model, surplus from a local school system--and named it Skillet. It was already green, so they just painted the name on the side and outfitted it inside as a communal living and sleeping space. Though it broke down frequently, the bus represented the group’s commitment to being a performance group.

Tommy Jarrell at Green Grass Clogger campsite, 1974 Charlotte-Mecklenburg Fiddler’s Convention, from the Doug Baker Collection.

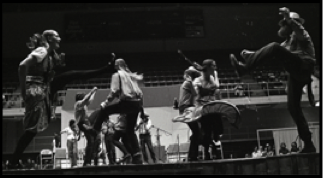

Green Grass Cloggers at 1974 Mountain Dance & Folk Festival, UNC-Asheville D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections/University Archives.

Skillet, 1974, from the Doug Baker Collection.

Top left: Skillet Breakdown on Interstate 81 in Virginia with the Swamp Root String Band, 1974; Top right: Skillet Interior with Brian Demarcus, 1974. Both photos from the Doug Baker Collection.

In their first decade, the cloggers befriended bands such as the Swamp Root String Band, the Red Clay Ramblers, the Highwoods Stringband, and the Hotmud Family. Often through festival friendships, the cloggers started getting invitations to dance farther and farther away from North Carolina. In 1977, they decided to form a traveling team of professional full-time dancers on the circuit of large folk festivals in the U.S. and Canada, with some trips overseas. The dancers who were available to join became the Road Team, and the ones who couldn’t, because of jobs and families, were the Home Team. Both were based in Greenville. The cloggers continued to absorb whatever dance knowledge they could during their travels, which included performing at the New Lost City Ramblers' twentieth anniversary celebration at Carnegie Hall in ’78. The same year, they also gained a new mentor--Robert Dotson of Sugar Grove, NC--whose Walking Step helped the cloggers enhance their footwork.

Robert Dotson, 2-13-2011, Appalachian State University Fiddlers Convention, Boone, NC, photo by Leanne E. Smith.

In 1980, the Road Team relocated to Asheville to make travel easier and to be closer to the old-time music culture still active in the mountains. They traveled internationally, taking trips to such places as South America and Asia, and developed some new routines to accommodate fewer than the eight dancers necessary for square dance figures. Marking the group’s fifteenth anniversary in 1986, they released the album, Through the Ears, featuring some of the cloggers’ musician friends, including Ralph Blizzard, Suzanne Edmundson, Carol Elizabeth Jones, Benton Flippen and the Smokey Valley Boys, Phil and Gaye Johnson, Bruce Molsky, and the Luke Smathers Band. The Road Team disbanded two years later and re-formed in Asheville to do local performances and occasional high-profile ones, such as at the Kennedy Center Honors in 1991. Meanwhile, the Home Team created new routines in the eighties, and in the nineties adapted the earlier choreography for a smaller membership.

Both the eastern and western groups of GGCs kept dancing the same routines, with some alterations that happened intentionally and some that occurred because some variations are inevitable in folk arts. At reunions in the eighties and nineties, members of the eastern and western groups had some interaction, but not much. Eventually, new members in both groups didn’t know each other. But by the early 2000s, several people who’d been in the group in the seventies eventually moved to the Asheville area and decided they wanted to dance together again. Their return led to a large thirty-fifth anniversary reunion in 2006.

Top left: Green Grass Cloggers at Philadelphia Folk Festival, 1976. Top right: GGC Home Team, 1987, Eno River Folk Festival, Durham, NC, from the Doug Baker Collection.

Top left: GGC Road Team, 1984, Kentucky Fried Chicken Bluegrass Festival, Louisville, KY; Top middle: GGC East Team, 1996, Red Springs Festival, Red Springs, NC, from the Rulifson Collection; Top right: GGC West Team, early 2000s.

Whereas the Green Grass style has maintained partner-based choreography and prioritized live music, the competition strain of clogging has evolved towards sequined costumes, intricate steps, and recorded pop music, and away from the partner-based figures. The earlier mountain round-dance clogging is isolated, and often superseded by structured competition styles. The traveling and teaching that Green Grass did in the seventies and eighties had such a wide influence that much of the clogging around the world that isn’t the competition precision style can be traced back to the hodgepodge Green Grass Cloggers through the spin-off groups that started among people who saw the cloggers and attended workshops at festivals. At a high point, about two hundred Green Grass-influenced groups existed--though today the closest descendants remaining in North Carolina are the Apple Chill Cloggers, the first spin-off in 1974, and the Cane Creek Cloggers, which formed in 1980. Dancers in numerous countries do steps like the Earl, Eddie, Jerry, and Karen’s Kick without always knowing they came from the Green Grass Cloggers, which means that, despite the opposition the early cloggers faced for being not “folk” enough, the Green Grass steps have entered folk tradition. In the early years of the Green Grass Cloggers, creation was a conscious choice, and today continuation is also a conscious choice.

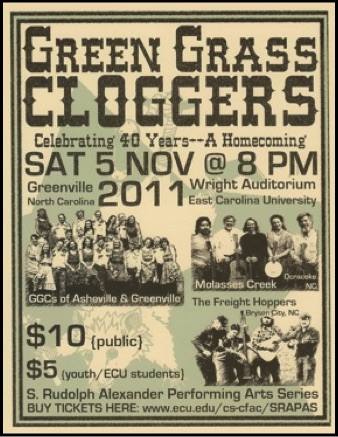

During the fortieth anniversary tour in 2011--named the Year of the Possum as a reference to the group’s 1978 pet possum Alfred--the GGCs grew to include three squares of dancers on stage together at venues such as Fiddler’s Grove, Greenville’s Sunday in the Park, Asheville’s Shindig on the Green, and the official reunion at the Hoppin’ John Old-Time and Bluegrass Fiddlers’ Convention at Shakori Hills. The November 2011 homecoming celebration at East Carolina University’s Wright Auditorium marked an onstage first for the group: they performed the earliest Green Grass routine with four squares of dancers. Between the fortieth and fifieth anniversaries, the group surpassed two hundred total members.

Recognitions for the Green Grass Cloggers include Western Carolina University’s 2008 Mountain Heritage Award, the Charlotte Folk Society’s 2011 Folk Heritage Award, a 2012 Community Traditions Award from the North Carolina Folklore Society, and in 2014, induction into the Blue Ridge Music Hall of Fame and America's Clogging Hall of Fame.

Poster for “Green Grass Cloggers: Celebrating 40 Years—A Homecoming” at ECU, 11-5-2011, design by Leanne E. Smith, with Molasses Creek photo by Ann Ehringhaus/Freight Hoppers press photo/possum by Suzannah Park.

I wanna try to keep it going … I’m gonna carry it on the best I can, long as I live.

--Robert Dotson, 13 February 2011

Green Grass Cloggers (many of the ones who performed), 9-17-2011, Fortieth Anniversary Reunion at Fifth Annual Hoppin’ John Old-Time & Bluegrass Fiddlers’ Convention, Shakori Hills, Silk Hope, NC, photo by Casey Challender.

Compiled by Leanne E. Smith, who is working on a narrative history of the Green Grass Cloggers (GGC). This version of the GGC story is adapted from "Green Grass Cloggers: Squared Up Counterculture Kids & the (Re)Forming of a Culture," a presentation she delivered at the North Carolina Folklore Society meeting on March 31, 2012. If you have stories you'd like to share, please send a message through this site that includes your contact information.

For a sampling of the Union Grove atmosphere, see this video compilation from the 1967 event.

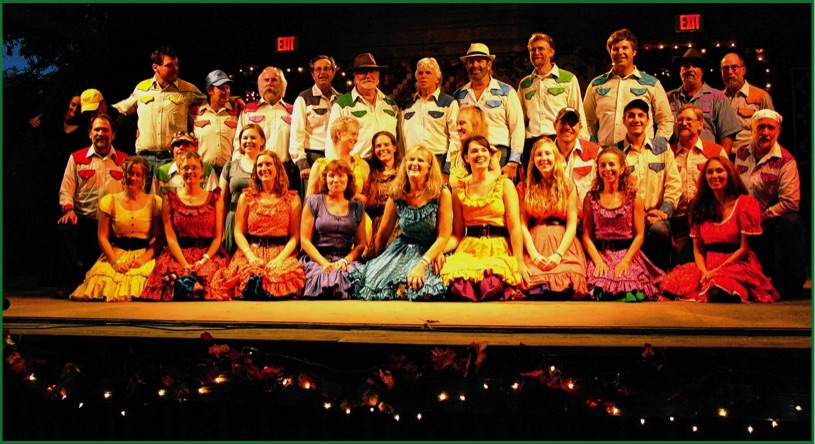

Green Grass Cloggers, 9-17-2022, Fiftieth Anniversary Reunion at Fifteenth Annual Hoppin’ John Old-Time & Bluegrass Fiddlers’ Convention, Shakori Hills, Silk Hope, NC.

Hoppin' Possums: Steps from the Green Grass Cloggers ties the stories back to their sources--with narrative history chapters unfolding through interviews with the sources of the steps: the GGC Basic Step, Dudley, Eddie, Earl, Karen’s Kick, Jerry, Possum Hop, Hunt Mallett, Rabie Hemby, and more from mentors Willard Watson, Hansel Aldridge, and Robert Dotson.

© 2024. Pilcrow, Possum & Persimmon Film Productions | © 2024. Incredible Feets Productions